Project Blog

Herzog August Bibliothek Blog Series – Popular Literature in Sixteenth Century Florence

By Anton Bruder

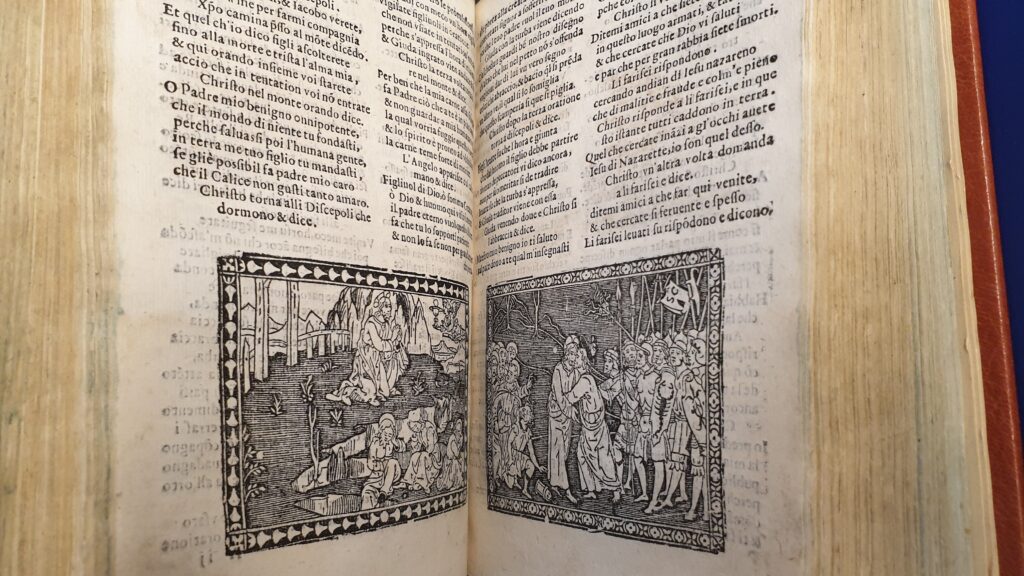

Description:CXII Poemetti popolari. Call number: Lk Sammelbd 64. 8vo. Sammelband of 112 pamphlets, all mid/late sixteenth century, mostly printed in Florence. Heavily illustrated with woodcuts throughout. Mostly roman and italic letter, some black letter and rotunda.

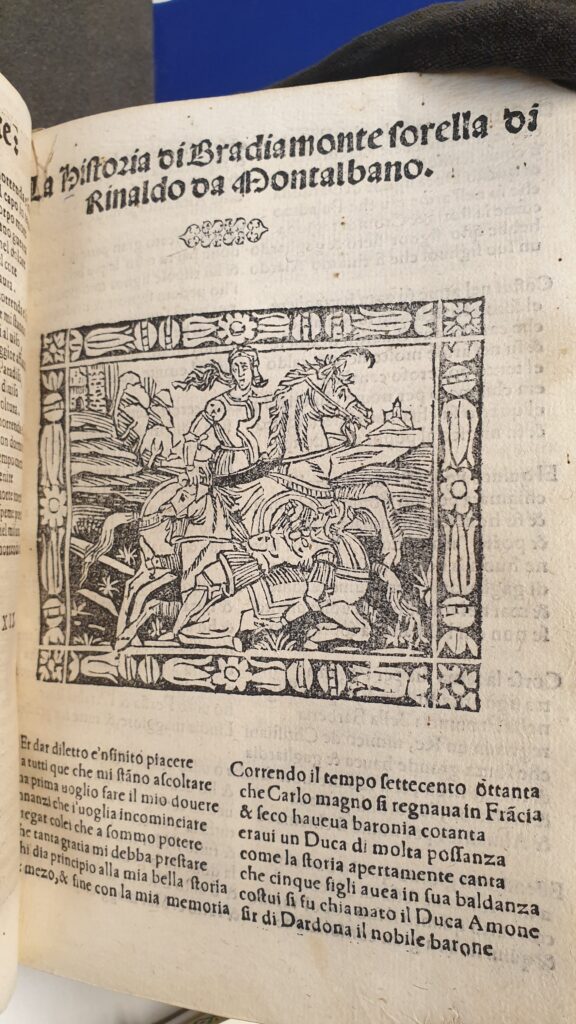

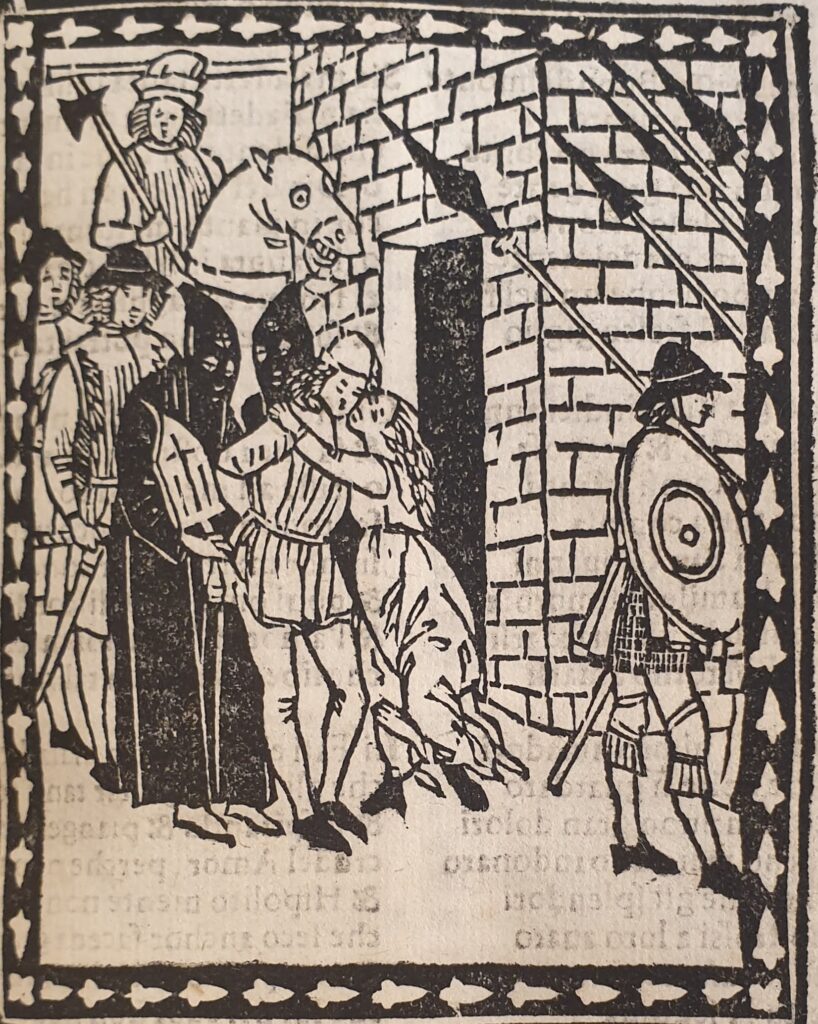

The chunky, leather-bound little fellow known as Lk Sammelbd 64 is a time capsule of popular reading in Florence around the time of Cosimo I de Medici. The artistic and intellectual hotbed of the Renaissance in the Quattrocento, by the mid sixteenth century Florence was now an industrious and bustling city of around 60,000 souls, many of whom frequently turned to reading as a leisure activity. This Sammelband (a book comprising separately printed or written works all bound together into a single volume), compiled at some point probably in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century and more recently rebound brings together around one hundred popular printed pamphlets of the sort widely enjoyed by the general public across early modern Europe. These include religious and moral tales, especially those taken from the adventures of the Saints (e.g. Historia et vita di Santo Alessio, La Storia e Oratione di Santo Stefano Protomartire, or La Storia, Oratione et Morte di San Giorgio, cavalier di Christo). Moral lessons could also be imparted by so-called exemplary novellas (e.g. La historia del Geloso, a story to warn readers against being jealous of women); generic morality tales or poems (e.g. La historia della Morte, a ‘danse macabre’ in the voice of Death himself); didactic poems (e.g. Le malitie et inganni di tutte quante l’Arte, about the various artisanal trades) and fables (e.g. La gran battaglia delli Gatti e delli Sorci [the great battle of the cats and the mice]). But reading didn’t always have to be so edifying. Less pious entertainment could be found in: stories from Greco-Roman mythology (e.g. La historia et favola d’Orpheo, or La historia di Giasone et Medea); and Roman history (e.g. the frequently sordid vitae of Roman nobles such as Lucretia or the emperor Vespasian). Nor did entertainment have to be exclusively drawn from the works of the ancients. Readers devoured short popular romances (e.g. Le sette dormienti or the Historia di Apollonio di Tiro); spin-offs of the chivalric epics, especially those by Ariosto and Boiardo (e.g. La historia di Bradiamonte sorella di Rinaldo da Montalbano, but also La morte di Buovo d’Antona); humorous tales (e.g. Le buffonerie de Gonnella, or the Novella del Graso legnaiuolo, molto piacevole e ridiculosa [the story of the fat carpenter, very pleasant and funny); so-called ‘prostitute literature’ (e.g. I Germini: Sopra quaranta meretrice [prostitutes] della citta di Firenze); and of course the convoluted stories of the many star crossed lovers, standard fare among Italian readers since Boccaccio’s Decameron: Pirramo and Tisbe, Prasildo and Tisbina, Ippolito Buondelmonti and Lianora di Bardi, Florindo and Chiarastella (Floire and Blanchefleur), and many others. All these texts are in the Tuscan vernacular; the vast majority are in verse, and most are heavily illustrated with crude but bold woodcuts. They are all relatively short (the shortest being between two and four pages long, and the longest only 60 pages), printed in two columns per page. All of these signs indicate a popular audience, learned and unlearned alike, but all sharing a taste for entertainment, adventure and edification through short works in verse. Most of these pamphlets, especially the shorter ones, would have been read once or twice before being discarded or repurposed (the printed page was often recycled throughout the early modern period) which means that relatively few of these texts and others like them, which would have been ubiquitous in early modern cities, survive today.